economists who predicted that a sustained period of high U.S. unemployment—and perhaps even recession—would be needed to bring down inflation are now “eating their words”.

This follows last month that a soft landing is “on track.” Claudia Sahm, a US macroeconomist, agrees. , she says:

The soft landing is not here yet. But it is in the bag.

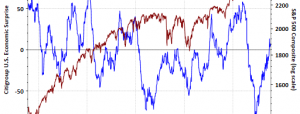

Markets seem to agree with the assessment by the Treasury Secretary and Ms Sahm; bonds have rallied like a bat of hell in the past month—temporarily pegged back by a semi-hot NFP report on Friday—and equities are in a good mood too. November, I am reliably told by the financial media, was the best month for a standard 60/40 portfolio … ever. And why wouldn’t markets be celebrating? Inflation in the developed world is now falling rapidly, and what was a significant inflation shock in core prices has now been turned on its head, as the charts below show.

It is a matter of almost trivial mathematical analysis that high inflation—this is to say the year-over-year rate in a statistically constructed price index—in the wake of series of one-off shocks will eat itself over time. This is to say, unless we assume that the shocks which pushed inflation higher in the first place will be repeated—which would be a misnomer since then they wouldn’t be shocks—the year-over-year rate in the price index has to fall back. The key question, however, is whether such shocks will shift the underlying trend so that the rate of inflation will be higher after the shock than before it.

This is exactly where we are now. Inflation is falling after the dual shocks of Covid stimulus and energy price boosting war in Ukraine. But we cannot yet say whether the underlying trend in inflation has shifted, and I don’t think we will be able to offer an answer until we see data for latter part of 2024, and indeed the start of 2025. That leaves an awful lot of time for markets to cheer a soft landing.

The argument over whether a soft landing is in the bag is well captured by the kinked Phillips Curve, which . A soft landing in this model is equivalent of moving from C to D, coupled with the crucial assumption that the rate of inflation at point D is either at target or sufficiently close to satisfy an independent inflation-targeting central bank that the work is done. If inflation at point D, however, is still too high for comfort, the path ahead is a painful one. If the economy has to move to point A to get inflation down to target, or a sufficiently acceptable level for the central bank and other economic stakeholders, policy has to tighten a lot—incurring a big rise in unemployment—to achieve a relatively small fall in inflation. This brings me back to a point that I have made on several occasions. The difference between a soft and a hard landing is not just a question of what the inflation rate at D is, but also whether central banks, and the wider economy and its institutions, are able to live with inflation that is higher, and quite possibly above the much hailed 2%, than before Covid.

Will we settle at point D? Or do we need to move to point A

Claudia Sahm, for her part, emphasizes that the inflation shock which is now fading was primarily driven by supply-side factors. In doing so, she is calling victory in the hotly contested debate about whether the surge in inflation after Covid and the war in Ukraine was due mainly to excessive demand stimulus by governments and central banks or supply-side disruptions. The spirit of her argument is captured by the shift from A to D in the chart above, where a relatively large fall in inflation is achieved with only a small fall in demand. But Ms. Sahm’s argument in its core really is best captured by shifts in the position of the supply curve, rather than its slope. What Ms. Sahm is really saying is that Covid and the War in Ukraine pushed the supply curve to the left, temporarily, and the fact that inflation is now falling means that it is shifting back. I am not sure this makes a lot of sense.

The supply side tends to be a lot less malleable than economists believe, or hope, indicating that if it has indeed shifted, it is not certain that we can assume it will fully shift back, and certainly not in a space of time that matters for cyclical policy. This is even more the case I think given geopolitics—de-risking, near-shoring, friend shoring—which now appear significantly less friendly to disinflationary global supply chains than in the past. If we factor-in that significant demand-side stimulus was, after all, administered during Covid, the macro environment suddenly looks structurally more inflationary, at least to me. Time will tell, but if we take Ms. Sahm at her word that the supply side was a key driver of the now-fading inflation shock, I would say that this increases the risk that a soft landing isn’t necessarily in the bag. This is especially the case since for an inflation-targeting central bank, inflation is inflation, whether it be driven by supply side or demand side effects.