“There is only one side of the market and it is not the bull side or the bear side but the right side.”

– Jesse Livermore

“At least us old men remember what a real bear market is like. The young men haven’t got a clue.”

– Jeremy Grantham

Image: John Solaro via

With regard to the stock market, some people are true perma-bears while others merely adopt a bearish outlook when indicators suggest trouble ahead. There’s a big difference between the two.

Call it nature, nurture, or something else, but some people have a reliably bearish outlook. You know before they say a word which way they will lean. The same is true of perpetual bulls.

Perma-bulls and perma-bears serve a useful function: They pay attention to information the rest of us may overlook because it doesn’t fit our own biases. Occasionally they unearth important information we should heed. So, it’s important not to discount everything the perma-types say.

As for me, I’m not perma-anything. Academic research confirms that my attitude is the proper one: cautious optimism. I look for opportunity where I can find it. And I find opportunity all the time, even though some of it is out of my financial reach. There would be a dearth of financial activity if investors and entrepreneurs did not aggressively seek opportunity. Perma-bears may never get around to joining in the fun (unless maybe they think gold will rise), and perma-bulls get periodically taken to the slaughterhouse when a business-cycle recession unfolds.

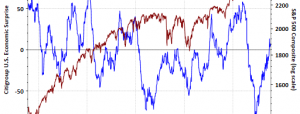

Today we’ll review some unusually bearish indicators from several sources, not all of them perma-bears, who lean bearish right now, even as US benchmarks post new highs. You can discount what follows if you wish – but don’t ignore it. Next week I’ll do an “All Things Bullish” letter. Please note, I am not necessarily calling for an end to this amazing bull market. I’m agnostic about that right now, because the traditional forecasting tools have been taken to the woodshed, an issue I’ve talked about in many previous letters. So we simply have to diversify trading strategies as opposed to being permanently long or short anything.

Now, before we jump into the bear pit, let me announce an event that some of you will want to attend. George Friedman of Geopolitical Futures is holding a special one-day conference on October 25 at the Yale Club in New York City. The theme is “Rising and Falling Powers: Separating Signal from Noise.” George says he will reveal a blueprint for the future international power structure. Click here for more information and to register.

OK, let’s take the plunge.

Evaluating Value

What’s a fair price for a share of stock? In theory, it’s easy to define. The fairest price lies at the intersection of the company’s supply and demand curves. The market price at any given moment reveals exactly where that point is. The averaged prices of all stocks in an index, appropriately weighted, tell us the same for market benchmarks.

In practice, the calculation is not so simple, because it is human beings who make the decisions – if not themselves then by telling their computers how to decide. Humans don’t always make rational choices. The stock market is the scene of a never-ending debate over who is the most rational actor.

My good friend Steve Blumenthal of CMG and I wrote a joint letter earlier this year called “Stock Market Valuations and Hamburgers.” Four months later, that letter is even more relevant. So are charts that my friends at Skenderberg Alternative Investments shared in their latest monthly review. (It’s free, by the way, and you should definitely ask to join their list. Just be aware, they seem to have a permanently bearish view, or at least they have recently. They are a fascinating source of all things bearish each month.)

We begin with this Bank of America chart. Look how many hours the average worker has to work in order to buy a notional share of the S&P 500. Amazing. Kudos to the B of A analyst who worked this data up.

You can see how valuations that are measured in this way skyrocketed in the 1990s bull market, then plunged in the following bear market and recession. They climbed again ahead of the 2008 crash yet could not reach their late-1990s peak – but now they have.

Equity capital is now at a historical high (going back to 1964) relative to labor. Two factors could tug the line down to a more normal level: sharply higher wages or sharply lower stock prices. Of course, I guess prices could go sideways for a few decades as wages rise. But on the probability scale I put that outcome pretty close to zero.