Unfortunately An ‘Official’ End To The Rising Dollar Isn’t More

TIC data confirms that “reflation” captured more than just pricing sentiment. It appears to have occurred in bank balance sheet activity, and related official sector UST transactions. As to the latter, official holdings of US$ assets did decline on net in March 2017, the latest figures, including more selling of UST’s. The scale of the decline was less than we had seen in previous months. In January 2017, for instance, total net “selling” was huge at almost $49 billion, but in the past two just $5.2 billion for February and $10.7 billion in March.

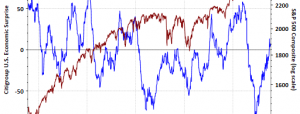

On a cumulative, rolling six-month basis, this method of ad hoc central bank measures intended (largely China but not just the Chinese) to try to offset private sector “dollar” retreat was at its lowest level since the six-month period ended June 2015. If there was an orthodox organization with the clout to declare officially an end to the “rising dollar”, they would likely have done so given these figures.

The reason for the lowered central bank pressure is undoubtedly a similar reduction in scale of bank balance sheet contraction. Going back to 2013, it had become common for banks to reduce their reported dollar liabilities (to foreign entities) in the final month of each quarter, some of those months with truly drastic reductions that almost in every case matched the outward monetary conditions globally.

In June 2015, for example, just as the official sector was about to be forced into more determined “selling UST’s”, TIC records an enormous $207 billion decline in these bank liabilities. Given that banks had in the two months prior during the same quarter only expanded by a total $116 billion combined, the net decline for Q2 2015 was a likewise enormous -$91 billion, leaving little mystery about the events that followed over the next few months.

In the latest quarter-end, March 2017, banks only withdrew $25 billion. Having added $12 billion in February and a hefty $113 billion in January, for Q1 2017 combined they contributed the largest representative increase in balance sheet capacity since the middle of 2014 – just prior to the start of the “rising dollar.”